Transcription: more fun than video games

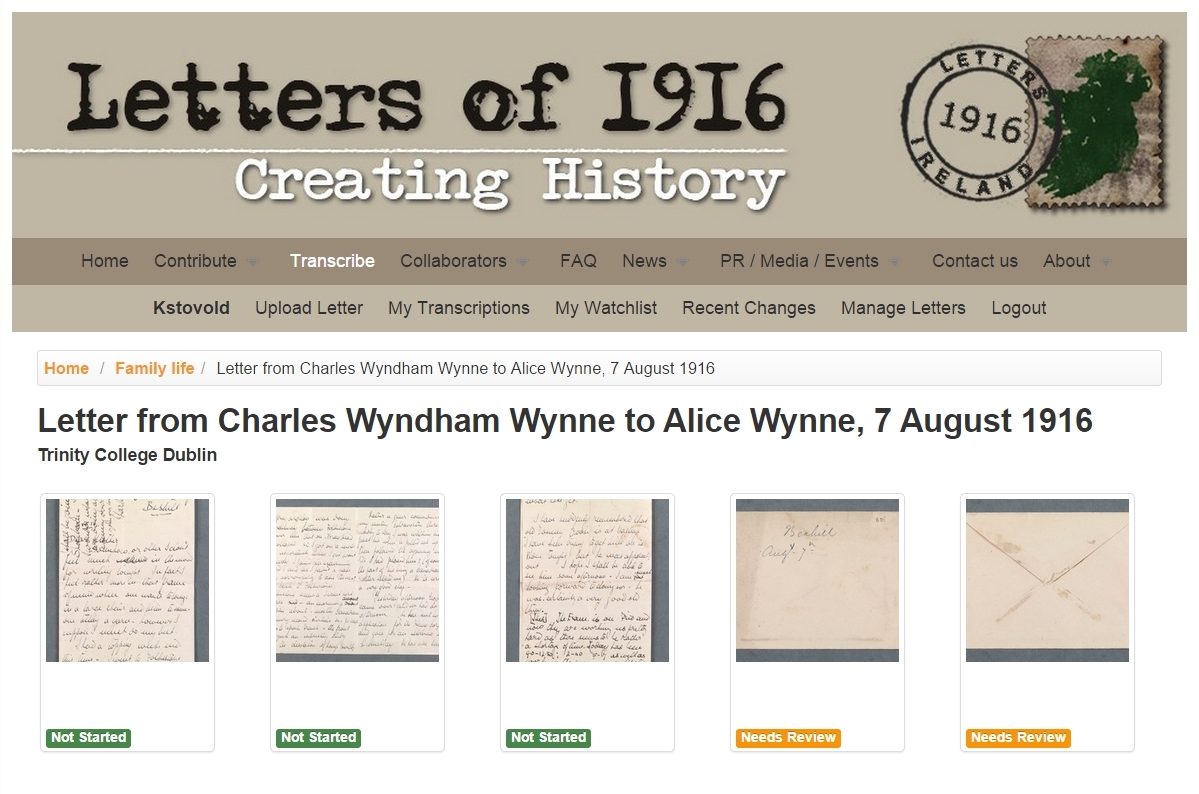

I recently took part in the crowdsourced historical project, “Letters of 1916“, in which volunteers transcribe letters and documents from around the time of Ireland’s famous Easter Rising. The letters are from both institutions and private collections in Ireland and abroad. It is said to be the first public humanities project in Ireland.

Documents have been scanned at a relatively high resolution. Volunteer transcriptionists register at the site, choose documents from a list, and begin the process of turning the contents from graphic representations into text. The contents thereby become searchable, indexable, and shareable. This is part of the global shift of scientific data from languishing in academic “silos”, removed from context and inaccessible to the majority of the population.

In his 2009 TED Talk, Tim Berners Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, implored researchers to share their discoveries. “Raw data now”, was the call. In 2010 he demonstrated what is possible when data becomes open.

My class was tasked with transcribing two letters apiece. While the request for more material seems open-ended, the available material at the time of the assignment was limited. The site is not set up for easy sorting, so this became one of the most time-consuming aspects of the endeavour. The only untouched letters I could find were bookkeeping accounts and ledger entries. Upon digging deeper, I found several letters had only had their envelopes transcribed. Because it had been many months since the envelope transcribers had touched the letters in question, they seemed fair game.

My two letters:

- Letter from Charles Wyndham Wynne to Alice Wynne, 7 August 1916

- Letter from J. K. Sheehan to the Secretary of the Information Bureau, 9 May 1916

The former appears to be a letter from an enlisted man in England written to his mother. He mentions bumping into an old mate and comments on the number of “khakis” (officers, presumably) present in town. The latter is a job inquiry from J. K. Sheehan, residing in San Francisco at the time, to the Secretary of the Information Bureau in Dublin. J. K. Sheehan was seeking information on how to apply for work connected to Dublin Castle.

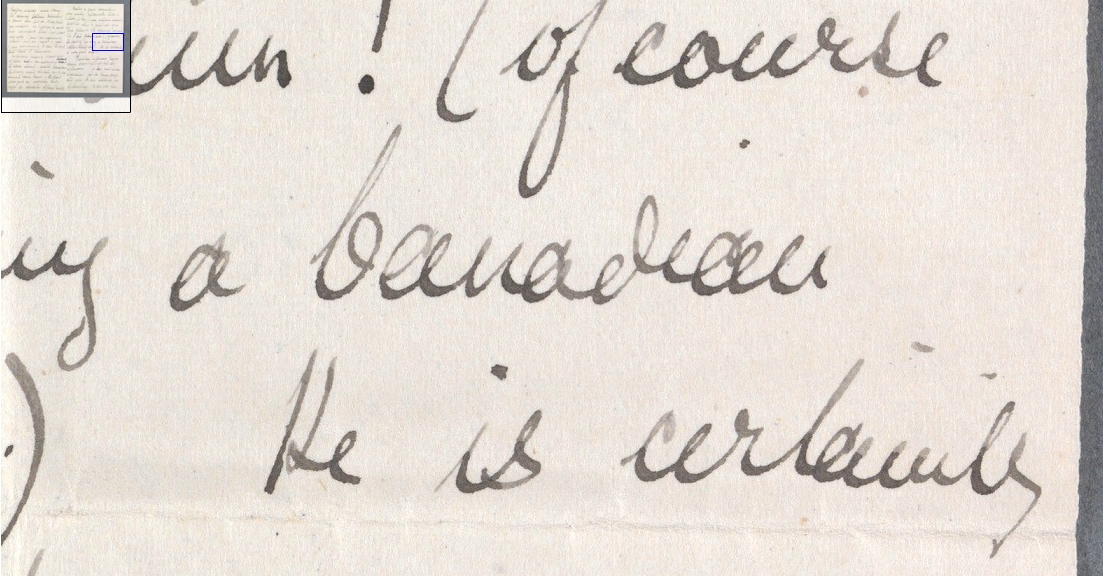

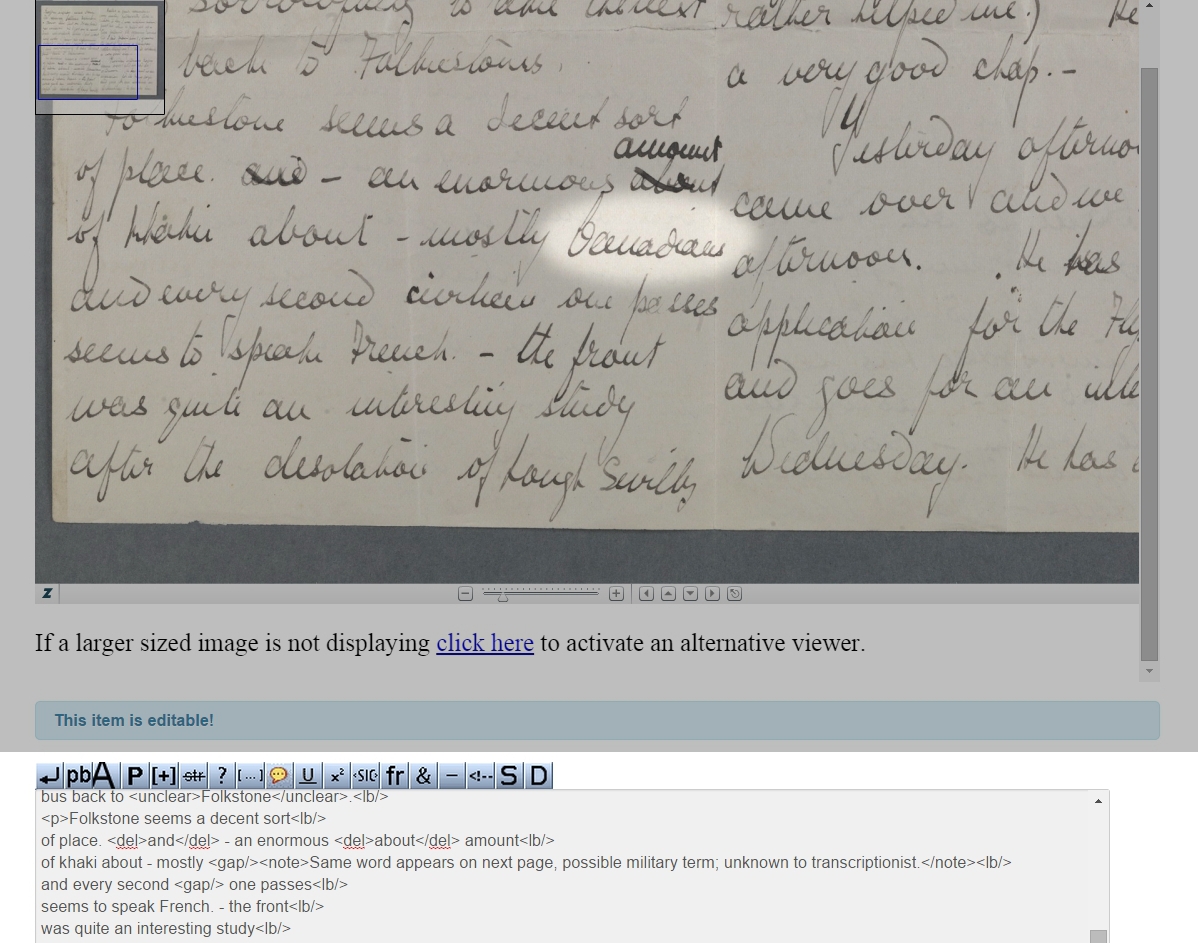

Each page receives its own screen, unless the scan is of a letter folded open like a book. The viewer can zoom in on different parts of the letter in order to more closely examine the handwriting. The grain of the paper, folds, smudges, even individual drops of ink, can be seen in great detail. One of my classmates reported detecting teardrops on one of the more heart-rending letters he transcribed.

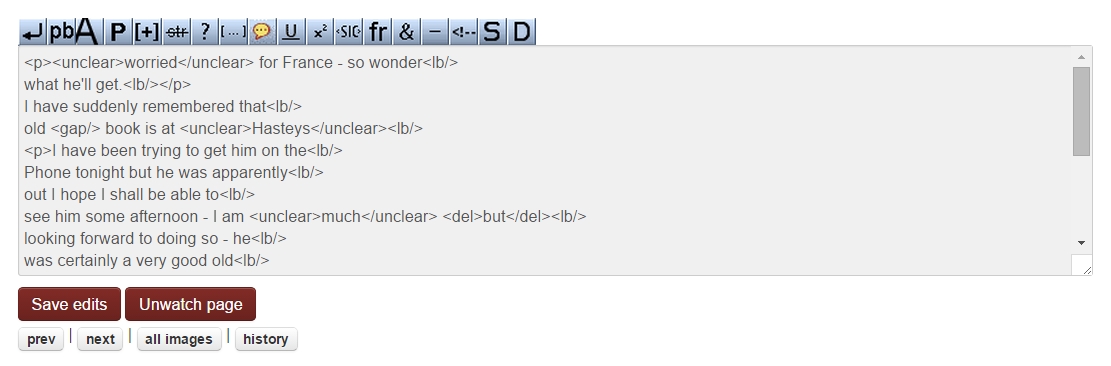

Below the image is the TEI-compliant XML editor in which the actual transcription takes place. Per the instructions on the site, after familiarising oneself with the buttons on the toolbar, one may simply begin transcribing. A knowledge of basic HTML and XML principles is useful, but not essential. The reasons for this being: 1) the toolbar makes it easy to insert code, and 2) every letter will be reviewed before being finalised.

To insert the code, one need only highlight a line or element (further clarification may be found in the site’s style guide) and click the relevant button on the toolbar. In terms of formatting, line breaks, paragraphs, and page breaks are important to call out. Elements of note include addresses, deletions by the original author, unusual spellings, illegible text, and margin notes, among other things. Notes from the transcriptionist, through use of the “User Comment” tag, can be included within classic HTML tags.

I found the User Comment option useful for pointing out to the reviewer that, despite marking a word as illegible, the same word appeared twice in the letter. The implication being that the issue may be more lack of knowledge on my part than an error on the author’s part. Indeed, it may be perfectly clear to someone more familiar with the vernacular of the time period. I have a background in the military, which is why the word “khakis” was an easy guess for me early on, but it’s possible this word is particular to the WWI era, or possibly to Irish and British soldiers in that location. A mention of soldiers from France may also indicate that the word is French.

Occasionally a place name, illegible upon initial viewing, could be deciphered by entering what little was known into a search engine. I knew, for example, that Mr. Charles Wyndham Wynne had taken the train from Dover to the town from which he was writing. Not being deeply familiar with the geography of Britain, I had a hard time deciphering the actual name. Google’s autofill suggestion helped me get it sorted.

Throughout the process, I found myself getting more familiar with the context and subject matter while simultaneously becoming more emotionally invested in the stories, brief as they are. I wanted to know more about Mr. Wynne and how his involvement in the war played out. I also wanted to know more about J. K. Sheehan and whether the petition for more information eventually led to employment at Dublin Castle. I hope the answers are revealed in other missives.

It was amazing to be reminded of how dear and precious such exchanges were in the days before electronic communication. The effort of writing by hand – presumably by fountain pen – posting, and hand delivering a letter, not to mention the wait between dispatches… There are so many points at which the postal connection could have broken down. Much more poignant than simply typing up a quick email and clicking ‘send’.

Just before embarking on the project, I had purchased a new video game, one I expected to arrest my attention for hours at a stretch, even distracting me from urgent assignments. It did not hold up in the face of this fascinating opportunity to connect with the past. The original intention of the project is to transform humanity into digital. Yet the digital served to pull me in and made the writers more human. Progress indeed.